Opiate use is deeply rooted in American history, with waves of addiction rolling over the vast North American landscape over the last two centuries. As a 2014 piece from The Atlantic noted, “with the exception of alcohol, opiate dependence is humanity’s oldest, most widespread and persistent drug problem.”

In order to fully understand the depth of that statement and where this latest epidemic of heroin use has come from, we will examine the journey that heroin has been on since the mid to late 19th century, where it is now and where it is headed.

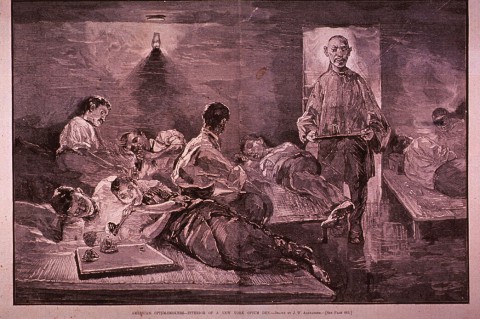

Railroads and Dens

Though opium had been experimented with and consumed for centuries, it wasn’t until about a decade before the start of the Civil War that morphine (another opium alkaloid) had become a fairly popular, commercially produced drug that was used to treat pain. Prior to that, opium had been commonly smoked in opium dens. Dens became more popular as Chinese immigrants came to the United States to work on its railroads, bringing with them the plant extract that had been in use in China since the seventh century. As use of these drugs spread, medical uses were being explored extensively.

At the same time, the hypodermic needle was invented and used to inject morphine as a pain reliever for soldiers who later became addicted, a condition that became known as “Soldier’s Disease.” Though an effective pain relief agent, the drug caused a morphine addiction epidemic in the years that followed, which doctors began to treat with heroin, first isolated in alkaloid chemistry in 1874. By the end of the century, heroin was being prescribed as a cure for alcoholism and had been synthesized in Germany by the Bayer Company.

The early 1900s saw doctors prescribing heroin for addiction and pain, and eventually, heroin addiction increases were so significant, particularly in the northeast’s industrial areas, that it was being used less and less as a medicine. By the 1920s, knowledge of heroin and its euphoric effects had spread beyond the medical community and the walls of opium dens.

It would blossom as a street drug in the 1930s, 40s and 50s with the beatnik and hipster scene, and that resurgence of demand for the drug was met with a supplier in the form of “The French Connection,” a group of Corsican gangsters working with the Sicilian Mafia to import heroin to users around the world. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, use of heroin grew significantly as a result.

At the same time, the United States was embroiled in the Vietnam War, introducing droves of soldiers to the drug while deployed and creating high rates of addiction for those returning from service. The New York Times subsequently ran a headline in 1971 reading, “G.I. Heroin Addiction Epidemic in Vietnam.”

This captured the attention of key figures in government, leading to President Nixon’s drug policy agenda that targeted heroin, calling it “public enemy number one.” That same year, Nixon ordered the creation of the first federal program for the treatment of opiate addictions with methadone.

Law enforcement ramped up its efforts to crack down on heroin use, but throughout much of the 1970s, the popularity of the drug grew as yet another new supply chain opened up from Southeast Asia’s “Golden Triangle,” a geographic area of opium production that overlaps the mountains which connect Myanmar, Laos and Thailand.

The 80s

The 1980s held two factors that temporarily slowed the growth of heroin use, particularly as an injectable.

The first was the proliferation of the AIDS virus. Its prevalence among intravenous drug users led many to turn their back on the drug and either begin smoking it, or experimenting with a new drug that took America’s inner cities by storm over the course of the decade – crack.

Crack cocaine use exploded, leading many to believe that clinics distributing methadone and focusing on heroin addictions would have to reprioritize their treatments to get people off this new drug. But about the time crack became the priority, heroin once again resurged into the marketplace as a way to come down from the days-long racing high of a crack binge.

Eventually, dealers began experimenting with a mixture, leading to the invention of the infamous “speedball,” a combination of crack and heroin that boasted a longer crack high with diminished intensity to the depression that followed.

A 1989 New York Times article quoted a rehab center spokesperson saying drug addicts were telling the staff that heroin saved their life because it brought them down from crack. In truth, however, they were looking at a population of drug addicts that were perpetually intoxicated.

As the dealers experimented with the addicting combination, the FBI reported a 741% increase in heroin and cocaine arrests from 1980-1995. Heroin was a focal point in the war on drugs, keeping it somewhat isolated to low income urban areas until the mid-1990s, when a new opiate went to market and brought the drug to the masses like never before.

It Started with an Injury

Dayton, Ohio native Jeremiah Hess believes he has been an addict since the age of 8, when he was sexually assaulted by three men. From that day forward, he began looking for an escape from the pain of that experience. He found it at the bottom of a bottle at a young age and as he grew older, he progressed to looking for it in the smoke from a joint or in lines of cocaine.

“After that happened, I’d steal liquor and do whatever I could to make the pain go away,” Hess said. “I couldn’t tell anybody. The older I got, I started on other things.”

At the age of 19, Hess was introduced to Vicodin when a doctor prescribed them to him because of an injury he sustained while at work.

“Once they prescribe them, you fall in love with them,” Hess said.

It didn’t take long for Hess to become addicted to opiates. When his prescriptions ran out, he struggled with withdrawals as he realized he was hooked. With his need for opiates becoming overwhelming, Hess turned to heroin.

“It doesn’t take long,” Hess said. “You get off them for a few days and you get sick. I knew about heroin for a long time and you always think it’s going to be cheaper. But in the end, you always want more. It’s not cheaper.”

Hess’s experience is far from unusual. The now 47-year old is part of a generation that was commonly prescribed opiates as part of a flawed system of treating pain. According to the journal ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 2011 saw 131 million prescriptions written for generic Vicodin and 31.9 million written for generic Percocet.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, an estimated 2.1 million people in the United States were suffering from substance use disorders related to prescription opioid pain relievers in 2012.

As a result, 2015 saw the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ask primary care doctors to cut back on prescribing these drugs unless it was absolutely needed. They recommended treating pain via physical therapy or at least prescribing lower doses.

“What we want is to just make sure that doctors understand that starting a patient on an opiate is a momentous decision,” CDC director Tom Frieden told the Washington Post. “The risks are addiction and death, and the benefits are unproven.”

Another Dayton native and former user of prescription opioids and heroin, who chose to remain anonymous, said that he was already addicted to the prescription opiates he bought from friends when he suffered a herniated disk in his back, and then was prescribed them legitimately by a doctor. It was, as he called it, “a happy accident.”

“It was almost as if being injured or ailing was a treat, because you knew you’d be getting good drugs. I used to have a steady prescription of hydrocodone for disk hernias. I also had a doctor that would prescribe liquid hydrocodone anytime I came in with a sore throat. For someone like me, it’s important that I admit to doctors that I have a history with opiate abuse before I’m treated for anything now.”

Given the addictive nature of opiates, many people are shocked by the fact that doctors have been so willing to prescribe them. A large part of the reason for this is thanks to another big player in the prescription opiate market.

You Might Also Enjoy: Heroin Death Rates Increasing for Middle-Aged White Americans

Oxycontin

When Purdue Pharma debuted its new prescription opiate in 1996, it entered a marketplace where synthetic opiates such as Percocet, Vicodin and Fetanyl had already lived for decades. This new brand of opiate – which on a molecular level is similar to heroin – from the little known pharmaceutical company headquartered in Stamford, Connecticut, exploded onto the scene, raking in $45 million in sales in the first year.

By the year 2000, that number ballooned to $1.1 billion. This spike naturally began to raise eyebrows as many people wondered how and why this drug was so successful. By 2010, sales were up to $3.1 billion and the opioid pill accounted for 30% of the painkiller market, as an estimated 254 million scripts for the drug were filled.

The first culprit in Oxycontin’s success was the marketing of the drug to doctors by the company. According to an article in The American Journal of Public Health titled, “The Promotion and Marketing of Oxycontin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy,” Purdue’s number of sales representatives increased from 318 to 671 between 1996 and 2000. A year later, the company was dumping $200 million into marketing of the drug.

Additionally, Purdue spent a good amount of time collecting data on doctors’ prescribing habits and organizing them by location to get a better idea of prescription patterns by state and country. By pinpointing doctors who prescribed the most pain medication for their marketing efforts, Purdue effectively pushed its drug into the hands of anyone who would take it, even doctors whose standards for prescribing an opiate were incredibly loose.

By the mid-2000s, Oxycontin was being prescribed for seemingly everything, whether it was chronic back pain, a routine tooth removal or post-operative discomfort. Purdue’s marketing efforts assured doctors that the painkiller was nearly addiction proof thanks to a time-release mechanism, which the company had used to gain FDA approval.

Using the time-release formula to say that the drug was less harmful led to nearly half of the doctors prescribing it being primary care doctors, or in other words, doctors that people trusted. This was a method of expanding the drug’s market potential past that of a heavy narcotic, originally thought to be more effective for pain experienced by cancer patients.

But it didn’t take long for addicts to find a way around the time-release formula. By crushing the pills and snorting, smoking or mixing them with water to create an injectable liquid similar to heroin, addicts could get their fix almost instantaneously.

But it didn’t take long for addicts to find a way around the time-release formula. By crushing the pills and snorting, smoking or mixing them with water to create an injectable liquid similar to heroin, addicts could get their fix almost instantaneously.

Abuse grew in proportion to the number of prescriptions, which were numerous to say the least. In King County, WA (Seattle area) alone, opioid prescriptions increased by 300% between 2000 and 2010.

The national picture was not much different and from 2001-2007, use of traditional heroin declined among adolescents, while federal heroin arrests fell by 32%. Oxycontin had taken its place and was popularly dubbed “hillbilly heroin.”

In Florida, pill mills pushing the drug became an epidemic in their own right. In 2010, the state was labelled the pill mill capital of the United States, with 856 pain clinics and 1,516 overdose deaths that year alone.

By that time, Purdue was taking a fair amount of flak for its marketing of the drug and had been trying to overhaul its image for a few years. In 2007, the company plead guilty to misleading doctors about the addictive nature of the drug, agreeing to pay $600 million in fines for defrauding and misleading the public. However, the damage had been done.

Pain Scores

The second major factor that led to a boom in Oxycontin prescriptions during the early 2000s was its ability to address a key issue for doctors themselves as they faced evaluations – the pain score.

Used as a measure of an individual’s level of pain, scores range from 0-to-10, with 10 being the worst possible pain and 0 being no pain at all. Doctors are sometimes judged on the collective score of their patients, leading to increased pain medication prescriptions in order to get the scores down.

“I was taught in residency, you give people as much pain medicine as they need,” Massachusetts-based Dr. Ruth Potee told Anthony Bourdain on his CNN show Parts Unknown. “You get them out of pain, we’ll judge your hospital, we’ll judge your emergency room based on your pain scores. That’s how we were taught. And we were also told these medicines aren’t all that addictive. We started handing out pills like crazy.”

The epidemic spread to all corners of the American landscape, but it hit insured, middle class suburbanites as hard as anyone.

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“One hundred million Americans have chronic pain. So we did a disservice as doctors and as prescribers.

We went forth with it and said prescribe it to everyone, they won’t get addicted. We know what we are doing. Guess what? We didn’t know what we were doing.”

Dr. Ruth Potee[/pullquote]

Author Sam Quinones released a new book in 2015 titled, “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s New Opiate Epidemic,” in which he outlined how the need to address pain went from sympathy for suffering cancer patients to a willingness to prescribe pills for anything. The following excerpt is from an interview Quinones did with Al Jazeera America:

Back in the 1980s and well into the 1990s, they developed a kind of pain revolution in this country that held that we were a country in pain. And what’s more is that we had the tools to deal with it in the form of prescription opioid pills – Vicodin, Percocet, oxycodone later. Science [said] that if you used these pills to treat pain that they would be – the buzzword was – virtually non-addictive.

It was on that basis that specialists, pain specialists, aided by pharmaceutical companies, convinced an entire generation of doctors to use these pills for pain of all kinds. First, it was terminal cancer pain; no one really felt that that was a bad idea. People were dying in agony. We needed to use these pills to relieve their suffering during their last and final days – clearly a decent and humane thing to do.

But then, that pendulum kept swinging to the point at where it became pills for the chronic pain, pills for all kinds of surgeries, pills for extracting wisdom teeth, athletic problems, all kinds of things like that. And this led to an enormous rising sea level, as a way that I put it in my book, of pills all across the country, in every corner of the country.

DEA Crack Down

The Drug Enforcement Administration began crackdowns on pill mills in 2011 during an operation they called “Pill Nation.” In a single operation, agents closed down 38 pill mills that were turning around hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of prescriptions a day.

Despite the increased enforcement efforts, this version of heroin continues to kill thousands of Americans. According to a 2015 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 16,000 Americans die annually from prescription opioid overdoses.

But the increase in law enforcement strategies and seizures to combat the epidemic has, in fact, made pills harder to come by and doctors more reluctant to write the scripts.

Change of Formula

Under pressure from the federal government, Purdue began attempting to address the issues surrounding the abuse of its popular drug and how it was being used as the DEA closed in on its unscrupulous prescribers. The company felt it needed to take measures in order to keep the doctors prescribing Oxycontin unconcerned over the status of legitimate practices as law enforcement scrutiny became more widespread.

By 2010, Purdue reformulated the drug so that it couldn’t be crushed. If mixed with water, it would turn into a gelatinous substance not suitable for injection. While there are still opioids that are not abuse resistant, the abuse resistant reformulation of oxycodone tablets has changed the marketplace. With fewer abuse resistant pills available and the street price of oxycodone ranging upwards of $1 per milligram, maintaining a pill addiction is more expensive than ever.

This combination of factors has once again led to a sharp increase in the use of the opiate’s inexpensive street counterpart – heroin. But the epidemic facing the country today looks much different than it did in previous decades and centuries.

Comments are closed.